Building systems for defense, aerospace, space, or advanced automotive platforms is never simple. These systems are complex by nature, often safety-critical, and usually developed under tight schedules and evolving customer expectations.

Yet many programs don’t fail because of poor engineering. They struggle because quality assurance is treated as something to “deal with later.”

Many programs don’t fail because the engineering is weak. They run into trouble because quality assurance is treated as something to deal with later. When QA planning is delayed, teams end up handling last-minute rework, delivery delays, audit issues, and the frustration of trying to add compliance to a product that is already built.

This article brings together the most commonly used QA frameworks across mission-critical industries and explains when to use which one, with the goal of helping founders, engineering managers, and program leaders avoid those late-stage surprises.

Why QA Becomes a Problem Late in the Program

When QA is not planned early, the symptoms tend to look very similar across programs:

- Compliance questions appear just before delivery

- Test strategies need to be reworked after implementation

- Hardware or software assumptions turn out to be invalid

- Teams feel pressure instead of confidence going into reviews

At that point, the cost of change is high. Architectures are fixed, hardware designs are frozen, and schedules are already committed.

In practice, QA thinking needs to start alongside requirements definition and documentation. That is the point where verification strategy, traceability, and tooling can still be aligned without disrupting the program.

Start by Identifying What You Are Actually Building

Before choosing any QA framework, teams need to answer a simple but often overlooked question:

What is the system we are validating?

Is it:

- Software only?

- Hardware only?

- Software and hardware together?

- A full system or system-of-systems?

The answer matters. A software-focused framework cannot adequately address hardware timing or physical interfaces, and system-level behavior cannot be assured by component-level testing alone. The right framework follows the nature of the system, not the other way around.

Functional and Non-Functional QA: Both Matter

Any meaningful QA approach looks at two sides of the system.

Functional testing focuses on behavior—interfaces, APIs, and expected outputs. This is often where automation and CI/CD pipelines provide the most value.

Non-functional testing looks at qualities such as reliability, performance, security, and availability. These tests are often long-running, scenario-based, and closer to real operational conditions. They frequently rely on manual or semi-automated execution.

Different QA frameworks emphasize different parts of this picture, which is why understanding their scope and overlap is essential.

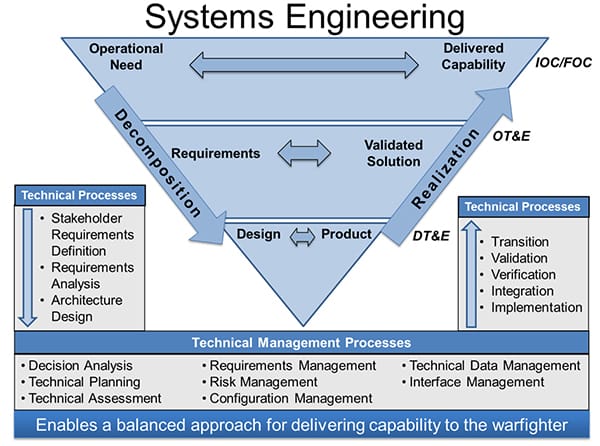

Understanding Framework Boundaries and Overlap

One of the most common sources of confusion in QA is the assumption that one standard will cover everything. In reality, most mission-critical programs use multiple frameworks together, each addressing a different layer of the system.

Some standards are clearly software-centric, focusing on how requirements flow into code, how interfaces are verified, and how traceability is maintained. Others are hardware-centric, dealing with timing, physical interfaces, and deterministic behavior. Then there are system-level frameworks that sit above both, ensuring that software and hardware come together correctly to meet overall system requirements.

For example, a software assurance framework is excellent at answering questions like:

- Are all software requirements implemented?

- Are APIs behaving as expected?

- Is verification traceable and repeatable?

But it does not explain how system requirements are allocated across software and hardware, or how integration issues are resolved. That is where system-level frameworks come in. They define how requirements flow down, how interfaces are controlled, and how gaps between software and hardware are handled.

Problems usually arise when teams:

- apply a component-level framework and assume system behavior is covered,

- or treat system-level guidance as optional until integration begins.

In practice, the overlap between frameworks is not accidental. It exists because system behavior cannot be assured without coordination across disciplines. Successful programs plan for this overlap early instead of discovering it during integration.

Traceability and Criticality: The Backbone of QA

Across all industries—whether aerospace, defense, space, or automotive—there is one concept that shows up again and again: traceability.

Traceability is not just a compliance checkbox. It is the only reliable way to demonstrate that:

- every requirement has been implemented,

- every requirement has been verified,

- And nothing critical has been missed.

Without traceability, teams rely on confidence and experience. With traceability, they rely on evidence.

Equally important is criticality classification, often expressed through concepts such as Design Assurance Levels (DAL) or similar mechanisms. Criticality determines how rigorous verification needs to be, not just whether a test exists.

High-criticality requirements demand:

- deeper verification,

- stronger independence,

- more complete documentation.

Lower-criticality requirements still need verification, but with proportionate effort. This distinction is important because it allows teams to focus rigor where it matters most, instead of treating all requirements the same.

Many late-stage surprises happen because traceability and criticality were not clearly defined early, forcing teams to revisit assumptions under schedule pressure.

Tooling, Automation, and CI/CD in Practice

Tools don’t define QA, but the right tools make disciplined QA possible at scale.

Most modern programs use a combination of tools to manage requirements, code, tests, and evidence. The goal is not to adopt every tool available, but to ensure that information flows cleanly from requirements to implementation to verification.

For test execution, teams typically rely on a mix of approaches:

Automated testing works well for functional verification, regression testing, and interface validation. Tools such as JUnit, TestNG, pytest, and Selenium are commonly used depending on the technology stack. When integrated into CI/CD pipelines using tools like Jenkins, GitHub Actions, or Bamboo, automation provides fast feedback and repeatability.

Manual testing still plays an important role, especially for non-functional scenarios. Long-running tests for availability, reliability under sustained load, performance under stress, or operational behavior are often difficult to fully automate. These tests require planning, patience, and clear acceptance criteria.

The most effective QA programs do not choose between manual and automated testing. They combine both, using automation for speed and consistency, and manual testing for depth and realism.

Putting It All Together: Mapping Systems to the Right QA Framework

Once teams understand what they are building, how functional and non-functional QA apply, and why traceability and criticality matter, the next logical question is:

Which QA framework applies to my system—and why?

This is where many programs struggle. Standards are often selected based on past experience, customer pressure, or what another project used, rather than a clear understanding of system type, level of criticality, and evidence expectations.

The table below brings together the most commonly used QA and compliance frameworks across aerospace, defense, space, automotive, and industrial domains. It shows:

- what each framework is intended to cover,

- the level at which it operates (software, hardware, system, or organization),

- and whether it is typically regulatory (REG), contractual (CON), or considered a best practice (BP).

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, but a practical reference to help teams make informed decisions early—before QA becomes a last-minute problem.

| Industry | System Covered & Primary Focus | What is Covered (Detailed Scope) | Std. Frame work |

REG| CON| BP |

| Aviation / Aerospace | Software assurance & certification | Software planning, high- and low-level requirements, architecture, source code, verification (reviews, analysis, testing), bidirectional traceability, configuration management, quality assurance, verification independence | DO-178C | REG |

| Electronic hardware design assurance | Hardware requirements, architecture, FPGA/ASIC lifecycle, design assurance, verification, traceability, configuration management | DO-254 | REG | |

| System development assurance | System requirements definition, functional allocation, system architecture, interface management, validation & verification planning | ARP4754A | REG | |

| System safety assessment | Functional Hazard Assessment (FHA), Preliminary System Safety Assessment (PSSA), System Safety Assessment (SSA), safety objectives, mitigation strategies | ARP4761 | REG | |

| Automotive | Functional safety of E/E systems | Hazard analysis and risk assessment (HARA), ASIL classification, safety goals, technical safety requirements, software and hardware safety lifecycle | ISO 26262 | REG |

| Process capability & supplier maturity | Development lifecycle assessment, supplier capability evaluation, process improvement and compliance measurement | ASPICE (ISO/IEC 330xx) | CON | |

| Industrial (Energy, Automation) | Functional safety of E/E/PE systems | Safety lifecycle management, SIL determination, hazard and risk analysis, functional safety validation | IEC 61508 | REG |

| Space | Mission, system & quality assurance | Mission assurance, system/software/hardware engineering lifecycle, verification planning, configuration control, operational readiness | ECSS (ECSS-Q / ECSS-E) | CON |

| Software engineering & assurance | Software lifecycle processes, verification and validation, safety, reliability, maintainability | NASA NPR 7150.2 | CON | |

| Systems engineering | Requirements definition, architecture development, trade studies, lifecycle reviews, verification and validation | NASA NPR 7123.1 | CON | |

| Defense / Military | System safety & risk management | Hazard identification, risk classification, mitigation planning, safety verification | MIL-STD-882E | CON |

| Software & system development processes | Development lifecycle definition, documentation, verification and review processes | MIL-STD-498 | CON | |

| Aerospace & Defense | Organizational & product quality management | Aerospace-grade QMS, supplier control, audits, corrective actions, continuous improvement | AS9100 | CON |

| Cross-industry (Aerospace, Automotive, Defense) |

Organizational quality management | Process standardization, audit readiness, corrective and preventive actions, continuous improvement | ISO 9001 | BP |

| Software lifecycle management | Software development, maintenance, operation, configuration management, quality assurance | ISO/IEC 12207 | BP | |

| System lifecycle management | Concept through disposal lifecycle processes, integration, verification, validation | ISO/IEC 15288 | BP | |

| Process maturity & capability improvement | Capability levels, organizational process improvement for development and services | CMMI | BP |