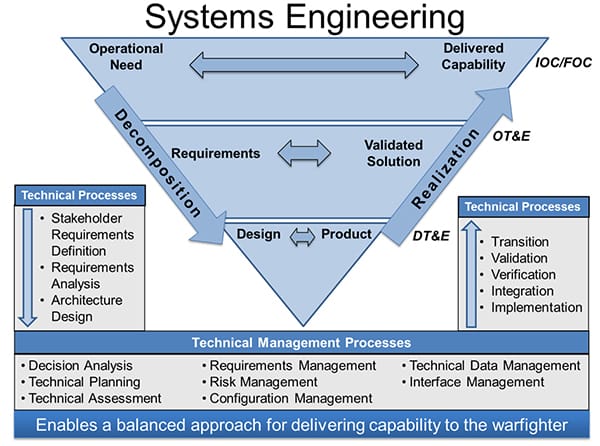

Systems engineering and Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) are often discussed as best practices that should be applied everywhere. In reality, they introduce structure, rigor, and overhead that only deliver clear value once a project crosses specific complexity thresholds.

The real question is not whether systems engineering is “good practice,” but when informal engineering intuition and ad-hoc coordination stop scaling, and system-level reasoning becomes necessary to control risk.

This article outlines five practical, experience-based indicators that a project has reached that point, along with guidance on when systems engineering may appear necessary but can reasonably be avoided.

Indicator 1: Multi-Disciplinary Technical Coupling

The strongest indicator that a project warrants systems engineering is tight coupling across multiple technical domains.

A project crosses into systems-engineering territory when it requires sustained coordination across domains such as:

- Hardware and electronics

- Embedded or real-time software

- Mechanical or industrial design

- Network and operational systems

- Sensors and control logic

- Security, safety, and protection mechanisms

- Reliability and fault-tolerance considerations

In such systems, decisions made in one domain produce non-obvious consequences in others. Local optimizations frequently degrade system-level behavior.

Once no single engineer or team can confidently understand the entire system without structured reasoning, informal approaches begin to fail. Systems engineering becomes necessary to make trade-offs explicit rather than reactive.

Indicator 2: Long System Lifecycle and High Cost of Change

Systems engineering becomes more valuable as system lifespan increases.

In long-lived systems, early architectural decisions tend to be frozen for years or decades, while the cost of change increases non-linearly after deployment. Development cost is often only a fraction of total lifecycle cost; operations, maintenance, verification, upgrades, and support dominate over time.

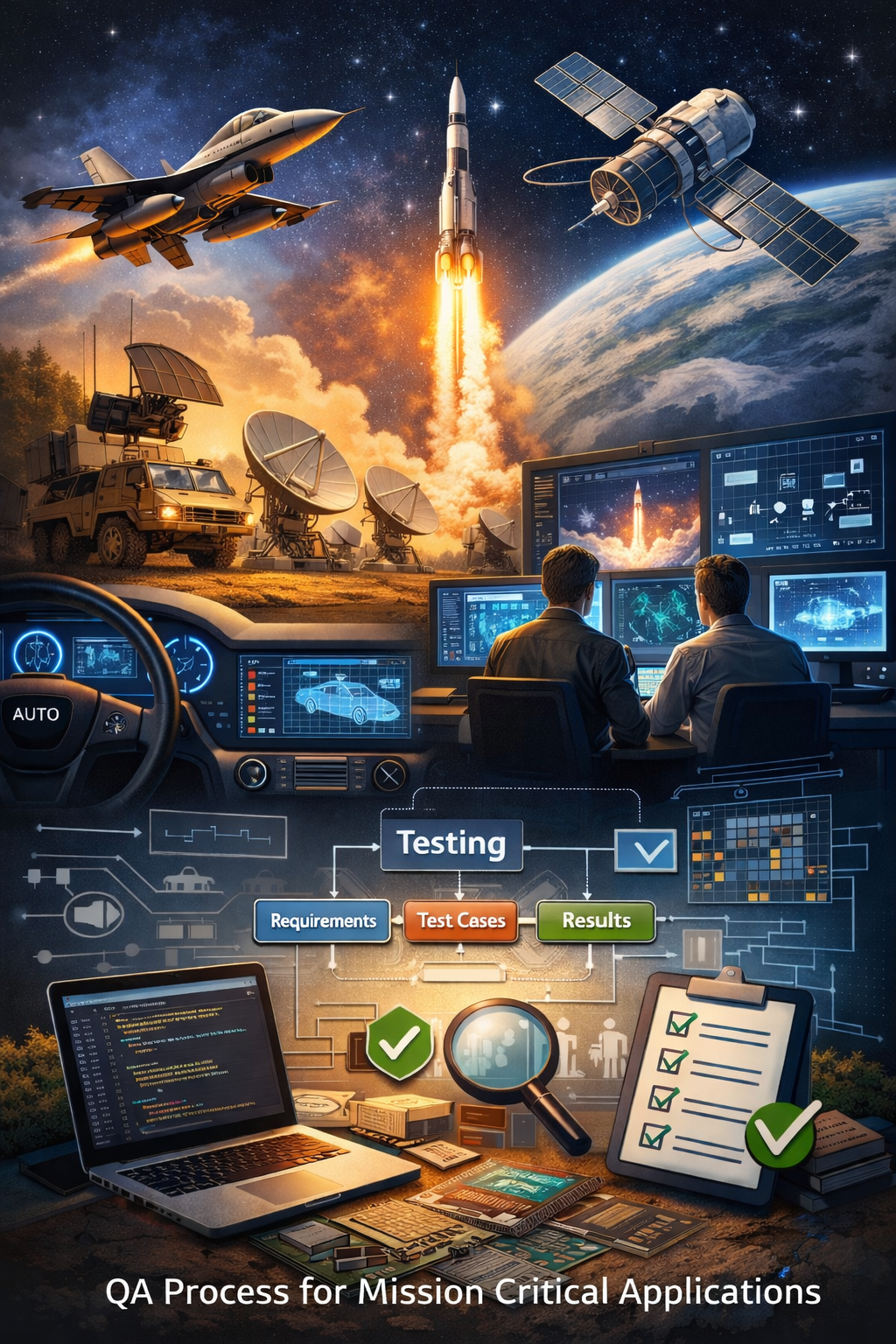

This applies strongly to:

- Space and satellite systems

- Aerospace platforms

- Defense systems

- Automotive architectures

- Mission-critical embedded products

In these environments, early system-level clarity is not an optimization exercise. It is a risk-control mechanism.

Indicator 3: Multiple Operational Contexts and Mission Scenarios

Another clear indicator is the presence of multiple operational contexts or mission scenarios.

Systems that must operate across different modes, environments, or usage conditions exhibit behavior that changes meaningfully with context. Requirements that appear simple in isolation often become ambiguous or conflicting when scenarios are considered together.

Common drivers include:

- Multiple operational modes or mission phases

- Environmental variability such as thermal, vibration, connectivity, or human interaction

- Nominal, degraded, and failure conditions

- Diverse stakeholders and user roles

As scenario count increases, edge cases stop being rare exceptions and become primary design drivers. Systems engineering provides the structure needed to reason about these interactions before they surface during integration.

Indicator 4: Delivery and Organizational Complexity as a Force Multiplier

Delivery complexity alone does not justify systems engineering, but it amplifies technical complexity when combined with the earlier indicators.

Relevant indicators include:

- Multiple development teams working in parallel

- Organizational or geographic separation

- Subcontractors or external delivery partners

- Contractual scope boundaries

In such environments, architecture becomes more than a technical artifact. It becomes a coordination mechanism. Clear system boundaries, assumptions, and interfaces reduce ambiguity, integration friction, and rework.

Delivery complexity is rarely the root cause, but it often accelerates failure when underlying system complexity already exists.

Indicator 5: Multi-Source Systems with Interface-Driven Technical Integration Risk

A project clearly warrants systems engineering when major subsystems are delivered by different teams, vendors, or organizations, and system behavior depends on the correctness of their interfaces, not just the internal correctness of each component.

In multi-source systems:

- Interfaces carry functional and behavioral meaning

- Timing, sequencing, and state transitions cross subsystem boundaries

- Local compliance does not guarantee system compliance

- Integration becomes the dominant technical risk

Even when individual components meet their specifications, system-level failures often arise from mismatched assumptions at interfaces: data semantics, timing constraints, failure handling, control authority, or performance margins.

At this point, interfaces effectively become the system.

Important distinction:

Multiple suppliers alone do not justify systems engineering.

Systems engineering becomes necessary when interfaces encode behavior, not just connectivity, and when correct system operation depends on cross-boundary interactions that cannot be validated through inspection or unit testing alone.

What Does Not Justify Systems Engineering

Equally important is knowing when systems engineering is not justified.

The following factors, by themselves, do not warrant MBSE or formal systems engineering.

Team Size Alone

A large team does not automatically imply system complexity. A well-understood product with stable interfaces may scale in people without introducing system-level uncertainty.

People count increases coordination effort, not system complexity.

Project Budget or Visibility

Large budgets raise the consequences of failure, but they do not create complexity by themselves. If the architecture is mature and well constrained, systems engineering may add limited value compared to strong execution discipline.

Money amplifies impact, not structural complexity.

High Volume of Requirements

A large number of requirements may reflect poor requirements hygiene rather than complex system behavior. Repetitive or parameterized requirements do not automatically justify architectural modeling.

Quantity of requirements is not the same as complexity of behavior.

Why Space, Aerospace, and Defense Almost Always Cross the Threshold

Most space, aerospace, and defense projects inherently exceed the complexity threshold that justifies systems engineering.

These systems typically involve:

- Tight coupling between hardware, software, electronics, and mechanical structures

- Sensors and real-time control loops

- Safety, reliability, and protection as first-order concerns

- Multiple operational modes and mission phases

- Harsh and variable environments

- Long lifecycles with limited opportunity for post-deployment correction

- Deployment or launch constraints that prevent full end-to-end testing

For space, aerospace, and defense domains, systems engineering is not overhead. It is necessary for assured delivery.

Closing Perspective

The decision to apply systems engineering or MBSE should never be driven by fashion, tools, or perceived complexity. It should be driven by where failure modes originate.

When complexity arises from coupling, longevity, variability, and integration risk, systems engineering provides a disciplined way to make assumptions explicit, manage trade-offs consciously, and control risk before it becomes irreversible.

Used selectively and pragmatically, systems engineering is not overhead.

It is how complex systems are made predictable.

FAQ – When Should Systems Engineering or MBSE Be Used?

Is systems engineering necessary for every project?

No. Systems engineering is most valuable when technical coupling, lifecycle length, operational variability, or integration risk is high. Small, well-understood, loosely coupled projects often do not justify the overhead.

Is project size or team size a good indicator for MBSE?

No. Team size and budget increase coordination complexity, not system complexity. MBSE is justified by coupling, variability, and integration risk—not headcount.

Can MBSE be overused?

Yes. Applying MBSE to low-risk or well-bounded systems can introduce unnecessary overhead without reducing real risk. Knowing when not to use MBSE is as important as knowing when to use it.

Do multi-vendor projects always require systems engineering?

Not always. Multiple suppliers alone do not justify MBSE. Systems engineering becomes necessary when system behavior depends on interface correctness across independently developed components.

Why are space, aerospace, and defense projects almost always system-engineered?

Because they combine multi-disciplinary coupling, long lifecycles, limited verification opportunities, multiple operational scenarios, and high cost of failure. Informal reasoning does not scale in these domains.

Is MBSE the same as systems engineering?

No. MBSE is one way to apply systems engineering principles. The need for systems engineering is driven by system complexity, not by the choice of tools.

What happens if systems engineering is not applied when it should be?

Risk is deferred rather than eliminated. Issues surface later during integration, verification, or operations, when correction is significantly more expensive and disruptive.